”What is not measured

does not count”

Martin Wolf, Financial Times

Post-Covid Fiscal Management.

Requires more comprehensive information for:

In the post-Covid world, government balance sheets are getting bigger as their fiscal positions weaken. The combination of governments being larger players in the economy and their fragile fiscal positions makes it even more important that their finances are well managed.

Better Decisions

There are two ways in particular that government financial management needs to be improved. First, financial management systems need to produce a more comprehensive information set that enables them to make better decisions. With the complexity of modern governments’ financial activities, this necessitates the use of accrual accounting as the basis for the whole budgetary and reporting system.

Better Asset Management

Second, the comprehensive information available with accrual accounting enables a step change in balance sheet management. A balance sheet approach to financial management means, first, a focus on net worth rather than debt as the key indicator of fiscal position, and second, the use of the additional information to achieve better asset management.

Ian Ball, the architect of the New Zealand financial reforms

Assets are critical for recovery

The post-Covid world will make proper accounting the politically inevitable choice, with;

1. Better Asset Management

2. Net Worth – the key fiscal indicator

3. Comprehensive information

Better asset management

Governments overlook the potential value of their Assets

In Rio de Janeiro, on the Avenida Atlantica, the splendid avenue that separates Copacabana beach from the large hotels that face the beach. The land on which the hotels are built is obviously very expensive because of its adjacency to the beach. At one point, squeezed between two of these hotels, there was a public school. Its location in front of the beach would almost surely distract the students from their school activities.

Relocating the school on Copacobana would be welfare improving

Furthermore, land with an extremely high market value was being used for an activity which, though socially important, could be located (to the benefit of the students’ learning) a couple of blocks away from the beach and on much cheaper land. This relocation would have released the land occupied by the school for the use with the highest market value.

Such a change would undoubtedly be welfare improving because it would raise national income while affording the government the possibility to build an equivalent or better school with the revenue from the sale of the land on which the school was built. At the same time, the students would move to a location where distractions would be much reduced.

Many SOEs are a Burden to Taxpayers and the Economy

Over the past decade, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have doubled in importance among the world’s largest corporations. They often deliver basic services such as water, electricity, and loans for families and small businesses. At their best, they can help promote higher economic growth and achieve development goals. However, many are a burden to taxpayers and the economy.

SOEs, taken as a whole, underperform and are less productive than private firms by one-third, on average.

![]() From: IMF Fiscal Monitor April 2020, State-Owned Enterprises – The Other Government

From: IMF Fiscal Monitor April 2020, State-Owned Enterprises – The Other Government

Governmental Accounting Standards Board is giving ruinously bad advice

America’s state and local governments are mismanaged: resources are wasted and obligations are hidden.

There are many reasons for this, but the official guidance published by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board deserves much of the blame. Politicians are encouraged to low-ball both the value of public assets and the cost of promises made to public-sector workers. It’s a recipe for poor governance, if not outright corruption. Adopting standards fundamentally similar to those used by private companies — as recommended by the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board — could make a big difference.

Professionally managed, assets could earn 3 percent of GDP in extra revenues each year

Once governments understand the size and nature of public assets, they can start managing them more effectively, raising considerable additional revenue. Also, public sector balance sheet analysis allows for better risk management and policymaking.

The Fiscal Monitor – Managing Public Wealth provides governments the initial tools to analyze the resilience of public finances. By identifying risks within the balance sheet, governments can act to manage or mitigate those risks early, rather than dealing with the consequences after problems occur. Balance sheet analysis raises the tenor of the policy debate, asking how public wealth can be better used to meet society’s economic and social goals.

Proper use of public commercial assets has been a core component of Singapore’s strategy to move the economy from developing to developed status in a single generation.

”The time is long past to end the focus on a few narrow numbers that led to chronic under-investment, as well as under-management of valuable assets. It is time for the UK debate on public finances to shift from being precisely wrong to trying to be roughly right.”

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, Read the full article

Net Worth – the key fiscal indicator

Stronger Net Worth gives greater fiscal flexibility

Governments with strong Net Worth positions – have

– Lower interest expenses

– Lower yields on their debt

– Greater fiscal flexibility

– More resilience to economic downturns

– Higher growth following a recession (3x faster)

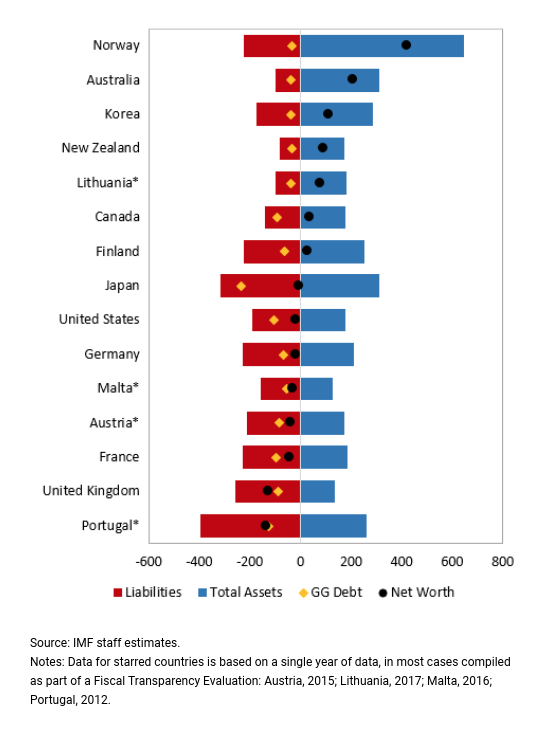

What governments owe and own

Advanced economies have larger balance sheets compared to emerging markets and low-income developing countries, and they also have larger liabilities and, on average, lower net worth

European net worth is relatively low

European countries have relatively low level of public sector net worth. General government net worth has, on average, worsened in euro area countries, since 2000. The median general government net worth moved – roughly – from positive 20 percent of GDP, in 2000, to negative 20 percent of GDP, in 2016.

US, UK Australia and Canada – negative

The governments of Australia, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom all have significantly negative net worth, and in the case of the UK and US the negative net worth is roughly the size of their respective GDPs.

Unsurprisingly in New Zealand ….

This is in stark contrast to New Zealand, that since the financial crisis in the 1980’s has steadily improved its fiscal situation, running surpluses, and improving its net worth (assets less liabilities), virtually every year except the four years following the global financial crisis and the Canterbury earthquakes.

Asset values in the EU are uncertain

Public assets across the European Union are, according to the European Commission, worth around 1xGDP. While data from the International Monetary Fund puts the value at 2xGDP.

There are probably many reasons why the values differ so fundamentally between the EC and the IMF. But the fact that the data is not based on audited accrual numbers and fails to capture most of the public real estate, is part of the problem.

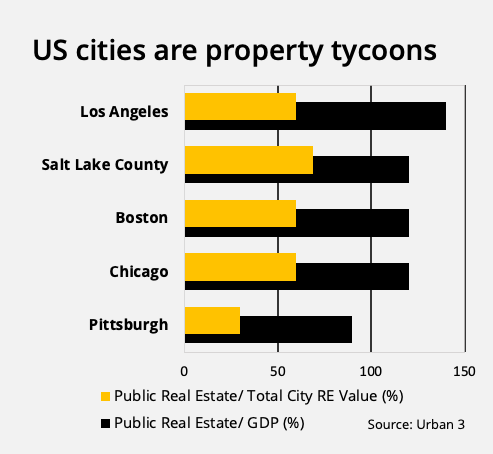

Indicative values of real estate are surprising

Available valuations of public real estate at the city level alone, would suggest that the value of the real estate within a city is equivalent to the value of the city’s GDP. In many US cities, indicative valuations show that the public sector owns around half the total real estate market in the respective jurisdiction. However, book values in the financial statements does not reflect this reality. As an example, the indicative value of the real estate alone in the City of Pittsburgh was 70 times that of the book value.

”The euro area would benefit from better information based on accrual accounting (IPSASB)”

Vitor Gaspar, International Monetary Fund, Read the full article

The IMF argues for accrual accounting

The IMF Government Finance Statistics Manual 2001 (GFSM) argues that a fully developed accrual accounting system could be introduced that provides for complete and fully integrated balance sheets to be prepared.

Comprehensive information

Relevant numbers enable better decisions

Relevant number are a prerequisite for financial management in the private as well as in the public sector. Just like any large corporation, a modern government is a highly complex institution that requires accrual accounting and audited numbers to ensure a sustainable long-term decision-making and management.

Critical for decision-making

Accrual accounting is the preferred set of information for financial decision-making (including budgetary decision making). It is also a means of improving transparency and accountability.

In the public sector the The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) works to improve public sector financial reporting worldwide through the development of IPSAS. For corporates, it is The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), that sets a single set of high-quality global accounting standards.

Integrating the balance sheet with the budget is key

Many governments that have moved to accrual reporting, still budget and make key decisions on the basis of cash flows and debt. They would benefit greatly from integrating the balance sheet with the budget.

“The tragedy of the UK reform process is that it has gone to a great effort to put in place better accounting systems, but then does not use the information in its fiscal decision-making.”

Ian Ball, Victoria University of Wellington, Read the full article

New Zealand - the public finance pioneer

New Zealand’s bold shift to accruals accounting was just the start of what has been a groundbreaking transformation.

The unfolding of New Zealand’s public sector reforms from the mid-1980s to today, begin with radical reforms in the 1980s in response to financial and political crises against a background of long term unsatisfactory economic performance.

The emphasis in government circles has been to provide information for politicians (and those that hold them to account) that is insightful and ranges far more widely than financial figures offering a limited rearview-mirror perspective. Hence the inclusion of new measures, such as environmental sustainability, plus an intergenerational dimension.

Arguably, this promotes long-term thinking among politicians and both encourages and enables them to make better decisions.

”The world’s first consolidated statement of public sector accounts on the accrual basis, played a vital part in persuading rating agencies to rate New Zealand’s sovereign debt at a higher level than they had previously indicated would be the case”

Impact on the Sovereign Rating

Would policy makers be incentivized to pursue the steps to improve the management of public commercial assets if this could lead to better ratings, thereby reducing borrowing costs that for many countries have become substantial and a further constraint on available fiscal space? A higher rating is also a signal that catches the attention of foreign investors, another reason that it is important to governments.

Visibility of the public sector balance sheet

Of course, the ratings methodologies of the three global rating agencies – S&P, Moody’s Investors’ Service, and Fitch Ratings do not incorporate the net worth of the public sector, in large part because they do not have visibility into the full scope of the public sector balance sheet. Since governments do not produce a complete and consolidated picture of all of their assets and liabilities, within the proper accounting framework to provide transparency, the agencies do not have the means to make an assessment based on what they cannot evaluate. Nor do they have the incentive to consider a balance sheet approach to ratings, as their well-established existing methodologies based on cash and debt have been “tried and tested” for decades. There is no competitive impetus or compelling rationale for the agencies to alter their rating methodologies.

Catch-22

Essentially, it is a classic “Catch-22 situation”: the rating agencies do not take public sector net worth into consideration in their assessments of sovereign creditworthiness because governments do not produce balance sheets, and the governments do not produce the balance sheets because the rating agencies do not need this information to produce their credit ratings. Evaluation of the public sector balance sheet as the starting point for the fundamental analysis of a government’s finances, and of its willingness and capacity to repay debt, would constitute a significant step-change in how the agencies conduct their business.

Enter the IMF?

This is not likely to come about without an external push, which perhaps might be exerted by the IMF were it to conclude that the full public sector balance sheet should be the proper basis for its debt sustainability analysis. Nonetheless, better management of public assets could still help governments improve their ratings – although indirectly, and in most cases over a long span of time before this could generate results that the agencies could measure, whether quantitatively or qualitatively. As a start, privatization or monetization of government assets, if of sufficient scale, could help to provide an uplift to the ratings by improving debt-related metrics, and demonstrating commitment to reform.

Benefit to society as a whole – and the economy

More efficiently managed public assets, by enhancing productivity, could also contribute to a higher rate of real GDP growth, generate dividends and other new revenue streams for the government budget, and potentially lower operating costs, thereby benefitting the fiscal and debt ratios.

To the extent that better management of public assets leads to the improved delivery of public goods and services to the citizens and is perceived by the rating agencies to enhance trust between the public and the government, this would further serve to improve their assessments of governance, policy effectiveness and institutional strength, all factors with considerable weight in the respective sovereign models.

By Hanan Amin-Salem, Global Head of Citi Sovereign Advisory

From: Citi Perspectives If Not Now, When? – How Better Management of Public Assets can Boost the Recovery

Historical Evidence

The history of financial accountability suggests that bad accounting comes back to haunt those who practise it both in business and in politics.

Transparency, accountability and good government can and do go together, and when they do, success can be relatively long-lasting. But the moral of Jacob Soll’s book is that such success never lasts, often because of a failure of political imagination or will.

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Making and Breaking of Nations’, by Jacob Soll